It should not be forgotten that this incident changed dramatically the course of the war and the occupation by the United States in Iraq. It may be considered as the turning point in the occupation of Iraq. This led to an abortive US operation to recapture control of the city and a successful recapture operation in the city in November 2004, called Operation Phantom Fury, which resulted in the death of over 1,350 insurgent fighters. Approximately 95 America troops were killed, and 560 wounded.

The U.S. military first denied that it has use white phosphorus as an anti-personnel weapon in Fallujah, but later retracted that denial, and admitted to using the incendiary in the city as an offensive weapon. Reports following the events of November 2004 have alleged war crimes, and a massacre by U.S. personnel, including indiscriminate violence against civilians and children.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fallujah - cite_note-17 This point of view is presented in the 2005 documentary film, “Fallujah, the Hidden Massacre”. In 2010, the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, a leading medical journal, published a study, which shows that the rates of cancer, infant mortality and leukemia exceed those reported in Hiroshima and Nagasaki[13].

The over 300 000 classified military documents made public by Wikileaks show that the “Use of Contractors Added to War’s Chaos in Iraq”, as has been widely reported by the international media recently.

The United States has relied and continues to rely heavily on private military and security contractors in conducting its military operations. The United States used private security contractors to conduct narcotics intervention operations in Colombia in the 1990s and recently signed a supplemental agreement that authorizes it to deploy troops and contractors in seven Colombian military bases. During the conflict in the Balkans, the United States used a private security contractor to train Croat troops to conduct operations against Serbian troops. Nowadays, it is in the context of its operations in Iraq and Afghanistan in particular that the State is massively contracting out security functions to private firms.

In 2009, the Department of Defense employed 218,000 private contractors (all types) while there were 195,000 uniformed personnel. According to the figures, about 8 per cent of these contractors are armed security contractors, i.e. about 20,000 armed guards. If one includes other theatres of operations, the figure rises to 242,657, with 54,387 United States citizens, 94,260 third country nationals and 94,010 host-country nationals.

The State Department relies on about 2,000 private security contractors to provide United States personnel and facilities with personal protective and guard services in Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel and Pakistan, and aviation services in Iraq. The contracts for protective services were awarded in 2005 to three PMSCs, namely, Triple Canopy, DynCorp International and the U.S. Training Center, part of the Xe (then Blackwater) group of companies. These three companies still hold the State Department protective services contracts today.

Lack of transparency

The information accessible to the public on the scope and type of contracts between the Government of the United States and PMSCs is scarce and opaque. The lack of transparency is particularly significant when companies subcontract to others. Often, the contracts with PMSCs are not disclosed to the public despite extensive freedom of information rules in the United States, either because they contain confidential commercial information or on the argument that non-disclosure is in the interest of national defense or foreign policy. The situation is particularly opaque when United States intelligence agencies contract PMSCs.

Lack of accountability

Despite the fact of their involvement in grave human rights violations, not a single PMSC or employee of these companies has been sanctioned.

In the course of litigation, several recurring legal arguments have been used in the defense of PMSCs and their personnel, including the Government contractor defense, the political question doctrine and derivative immunity arguments. PMSCs are using the Government contractor defense to argue that they were operating under the exclusive control of the Government of the United States when the alleged acts were committed and therefore cannot be held liable for their actions.

It looks as if when the acts are committed by agents of the government they are considered human rights violations but when these same acts are perpetrated by PMSC it is “business as usual”.

The human rights violation perpetrated by private military and security companies are indications of the threat posed to the foundations of democracy itself by the privatization of inherently public functions such as the monopoly of the legitimate use of force. In this connection I cannot help but to refer to the final speech of President Eisenhower.

In 1961, President Eisenhower warned the American public opinion against the growing danger of a military industrial complex stating: “(...) we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defence with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together”.

Fifty years later, on 8 September 2001, Donald Rumsfeld in his speech in the Department of Defence warned the militaries of the Pentagon against “an adversary that poses a threat, a serious threat, to the security of the United States of America (...) Let's make no mistake: The modernization of the Department of Defense is (...) a matter of life and death, ultimately, every American's. (...) The adversary. (...) It's the Pentagon bureaucracy. (...)That's why we're here today challenging us all to wage an all-out campaign to shift Pentagon's resources from bureaucracy to the battlefield, from tail to the tooth. We know the adversary. We know the threat. And with the same firmness of purpose that any effort against a determined adversary demands, we must get at it and stay at it. Some might ask, how in the world could the Secretary of Defense attack the Pentagon in front of its people? To them I reply, I have no desire to attack the Pentagon; I want to liberate it. We need to save it from itself."

Rumsfeld should have said the shift from the Pentagon’s resources from bureaucracy to the private sector. Indeed, that shift had been accelerated by the Bush Administration: the number of persons employed by contract which had been outsourced (privatized) by the Pentagon was already four times more than at the Department of Defense.

It is not anymore a military industrial complex but as Noam Chomsky has indicated "it's just the industrial system operating under one or another pretext”.

The articles of the Washington Post “Top Secret America: A hidden world, growing beyond control”, by Dana Priest and William M. Arkin (19 July 2010) show the extent that “The top-secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work”.

The investigation's findings include that some 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States; and that an estimated 854,000 people, nearly 1.5 times as many people as live in Washington, D.C., hold top-secret security clearances. A number of private military and security companies are among the security and intelligence agencies mentioned in the report of the Washington Post.

The Working Group received information from several sources that up to 70 per cent of the budget of United States intelligence is spent on contractors. These contracts are classified and very little information is available to the public on the nature of the activities carried out by these contractors.

The privatization of war has created a structural dynamic, which responds to a commercial logic of the industry.

A short look at the careers of the current managers of BAE Systems, as well as on their address-books, confirms we are not any longer dealing with a normal corporation, but with a cartel uniting high tech weaponry (BAE Systems, United Defence Industries, Lockheed Martin), with speculative financiers (Lazard Frères, Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank), together with raw material cartels (British Petroleum, Shell Oil) with on the ground, private military and security companies[14].

The majority of the private military and security companies has been created or are managed by former militaries or ex-policemen for whom it is big business. Just to give an example MPRI (Military Professional Resources Incorporation) was created by four former generals of the United States Army when they were due for retirement[15]. The same is true for Blackwater and its affiliate companies or subsidiaries, which employ former directors of the C.I.A.[16]. Social Scientists refer to this phenomenon as the Rotating Door Syndrome.

The use of security contractors is expected to grow as American forces shrink. A July report by theCommission on Wartime Contracting, a panel established by Congress, estimated that the State Department alone would need more than double the number of contractors it had protecting the American Embassy and consulates in Iraq.

“Without contractors: (1) the military engagement would have had to be smaller--a strategically problematic alternative; (2) the United States would have had to deploy its finite number of active personnel for even longer tours of duty -a politically dicey and short-sighted option; (3) the United States would have had to consider a civilian draft or boost retention and recruitment by raising military pay significantly--two politically untenable options; or (4) the need for greater commitments from other nations would have arisen and with it, the United States would have had to make more concessions to build and sustain a truly multinational effort. Thus, the tangible differences in the type of war waged, the effect on military personnel, and the need for coalition partners are greatly magnified when the government has the option to supplement its troops with contractors”[17].

The military cannot do without them. There are more contractors over all than actual members of the military serving in the worsening war in Afghanistan.

CONCLUSIONS OF THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE impact of Private Security Contracting on U.S. Goals in Afghanistan[18]

Conclusion I: The proliferation of private security personnel in Afghanistan is inconsistent with the counterinsurgency strategy. In May 2010 the U.S. Central Command's Armed Contractor Oversight Directorate reported that there were more than 26,000 private security contractor personnel operating in Afghanistan. Many of those private security personnel are associated with armed groups that operate outside government control.

Conclusion 2: Afghan warlords and strongmen operating as force providers to private security contractors have acted against U.S. and Afghan government interests. Warlords and strongmen associated with U.S.-funded security contractors have been linked to anti Coalition activities, murder, bribery, and kidnapping. The Committee's examination of the U.S. funded security contract with ArmorGroup at Shindand Airbase in Afghanistan revealed that ArmorGroup relied on a series of warlords to provide armed men to act as security, guards at the Airbase.

Open-ended intergovernmental working group established by the HR Council

Because of their impact in the enjoyment of human rights the Working Group on mercenaries in its 2010 reports to the UN Human Rights Council and General Assembly has recommended a legally binding instrument regulating and monitoring their activities at the national and international level.

The motion to create an open ended intergovernmental working group has been the object of lengthy negotiations, in the Human Rights Council, led by South Africa in order to accommodate the concerns of the Western Group, but primarily those of the United States and the United Kingdom and of a lot a pressure exerted in the capitals of African countries supporting the draft resolution. The text of the resolution was weakened in order to pass the resolution by consensus. But even so the position of the Western States has been a “fin de non recevoir”.

The resolution was adopted by a majority of 32 in favour, 12 against and 3 abstentions. Among the supporters of this initiative are four out of the five members of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, China and South Africa) in addition to the African Group, the Organization of the Islamic Conference and the Arab Group.

The adoption of this resolution opens an interesting process in the UN Human Rights Council where civil society can participate in the elaboration of an international framework on the regulation, monitoring and oversight of the activities of private military and security companies. The new open ended intergovernmental working group will be the forum for all stakeholders to receive inputs, not only the draft text of a possible convention and the elements elaborated by the UN Working Group on mercenaries but also of other initiatives such as the proposal submitted to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, the Montreux Document and the international code of conduct being elaborated under the Swiss Initiative.

However, the negative vote of the delegations of the Western Group indicates that the interests of the new staggering security industry – its annual market revenue is estimated to be over USD one hundred billion – have been quite well defended as was the case in a number of other occasions. It also shows that Western governments will be absent from the start in a full in-depth discussion of the issues raised by the activities of PMSC.

We urge all States to support the process initiated by the Council by designating their representatives to the new open-ended intergovernmental working group, which will hold its first session in 2011, and to continue a process of discussions regarding a legally binding instrument.

The participation of the UK and USA main exporters of these activities (it is estimated at 70% the industry of security in these two countries) as well as other Western countries where the new industry is expanding is of particular importance.

The Working Group also urges the United States Government to implement the recommendations we made, in particular, to:

support the Congress Stop Outsourcing Security (SOS) Act, which clearly defines the functions which are inherently governmental and that cannot be outsourced to the private sector;

rescind immunity to contractors carrying out activities in other countries under bilateral agreements;

carry out prompt and effective investigation of human rights violations committed by PMSCs and prosecute alleged perpetrators;

ensure that the oversight of private military and security contractors is not outsourced to PMSCs;

establish a specific system of federal licensing of PMSCs for their activities abroad;

set up a vetting procedure for awarding contracts to PMSCs;

ensure that United States criminal jurisdiction applies to private military and security companies contracted by the Government to carry out activities abroad; and

respond to pending communications from the Working Group.

Notes

[1] Blackwater Worldwide abandoned its tarnished brand name in order to shake its reputation battered by its criticized work in Iraq, renaming its family of two-dozen businesses under the name Xe’, see Mike Baker, ‘Blackwater dumps tarnished brand name’, AP News Break, 13 February 2009.

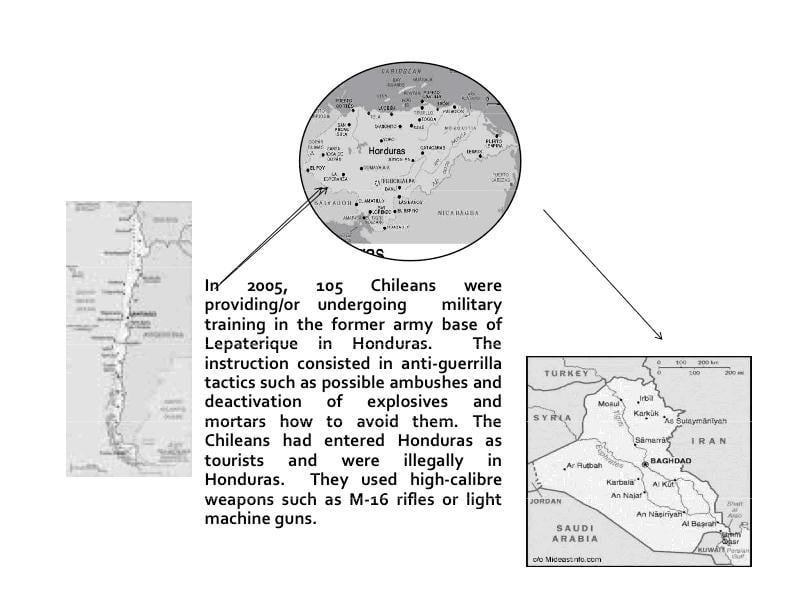

[2] URG, an Australian private military and security company, uses a number of ex military Chileans to provide security to the Australian Embassy in Baghdad. Recently one of those “private guards” shot himself, ABC News, reported by La Tercera, Chile, 16 September 2010.

[3]J.Mendes & S Mitchell, “Who is Unity Resources Group?”, ABC News Australia, 16 September 2010.

[4] Case 8:08-cv-01696-PJM, Document 103, Filed 07/29/10. Defendants have filed Motions to Dismiss on a number of grounds. They argue, among others, that the suit must be dismissed in its entirety because they are immune under the laws of war, because the suit raises non-justiciable political questions, and because they possess derivative sovereign immunity. They seek dismissal of the state law claims on the basis of government contractor immunity, premised on the notion that Plaintiffs cannot proceed on state law claims, which arise out of combatant activities of the military. The United States District Court for the district of Maryland Greenbelt Division has decided to proceed with the case against L-3 Services, Inc. It has not accepted the motions to dismiss allowing the case to go forward.

[5] Mission to the United States of America, Report of the Working Group on the use of mercenaries, United Nations document,A/HRC/15/25/Add.3, paragraphs 22.

[6] James Risen and Mark Mazzetti, “Blackwater guards tied to secret C.I.A. raids ”, New York Times, 10

December 2009.

[7] Adam Ciralsky, “Tycoon, contractor, soldier, spy”, Vanity Fair, January 2010. See also Claim No. HQ08X02800 in the High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, Binyam Mohamed v. Jeppesen UK Ltd, report of James Gavin Simpson, 26 May 2009.

[8]ACLU Press Release, UN Report Underscores Lack of Accountability and Oversight for Military and Security Contractors, New York, 14 September 2010.

[9] The reports also indicates that the Revenues of DynCorp for 2006 were of USD 1 966 993 and for 2009 USD 3 101 093

[10] Mission to Ecuador, Report of the Working Group on the use of mercenaries, United Nations document, A/HRC/4/42/Add.2

[11] A number of the persons involved in the attempted coup were arrested in Zimbabwe, other in Equatorial Guinea itself the place where the coup was intended to take place to overthrow the government and put another in its place in order to get the rich resources in oil. In 2004 and 2008 the trials took place in Equatorial Guinea of those arrested in connection with this coup attempt, including of the British citizen Simon Mann and the South African Nick du Toit. The President of Equatorial Guinea pardoned all foreigners linked to this coup attempt in November 2009 by. A number of reports indicated that trials failed to comply with international human rights standards and that some of the accused had been subjected to torture and ill-treatment. The government of Equatorial Guinea has three ongoing trials in the United Kingdom, Spain and Lebanon against the persons who were behind the attempted coup.

[12] Report of the Working Group on the use of mercenaries, Mission to Honduras, United Nations document A/HRC/4/42/Add.1.

[13] Wikipedia

[14] Mercenaries without borders by Karel Vereycken, Friday Sep 21st, 2007

[15] Among which General Carl E. Vuono, Chief of the Army during the Gulf War and the invasion of Panama; General Crosbie E. Saint, former Commander in Chief of the USA Army in Europe and General Ron Griffith. The President of MPRI is General Bantant J. Craddock.

[16] Such as Cofer Black, former Chief of the Counter Terrorism Center; Enrique Prado, former Chief of Operations and Rof Richter, second in command of the Clandestine Services of the Company

[17] Article published in the Spring 2010 issue of the University of Chicago Law Review, titled "Privatization's Pretensions" by Jon D. Michaels, Acting Professor of Law at the UCLA School of Law

[18] INQUIRY INTO THE ROLE AND OVERSIGHT OF PRIVATE SECURITY CONTRACTORS IN AFGHANISTAN, R E P O R T TOGETHER WITH ADDITIONAL VIEWS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE, 28 September 2010